PUBLICATIONS

2005

Book: ‘Colour Matters’, abstract art

The book ‘Color Matters’ published on the occasion of the exhibitions ‘Abstract Salon – Part One’ and ‘Abstract Salon – Part Two’. These exhibitions took place in september/october 2004 and april/may 2005, in Kunstruimte 09 – Herebinnensingel 9 – Groningen.

Abstract Salon, part one

Thomas Rajlich, Tineke Bouma, Rom Gaastra, JCJ Vanderheyden, Jus Juchtmans, Betty Simonides, Mark de Weijer, Alie Waalkens, Martin Scholte, Sybille Pattscheck, Vincent Hamel.

Abstract Salon, part two

Joost van Oss, Ton Mars, Marian Breedveld, Kees Visser, Clary Stolte, Judith de Vet, Vosenvanderveen, W.J.M. Kok, Gerard Kodde, Jan van der Ploeg.

Text ‘Some notes’: Jacob van der Veen / jd vos (Curators Kunstruimte 09).

Text ‘To Jacob and Joke’: Han Steenbruggen (Curator Groninger Museum).

Issued by: Stichting Kunstruimte 09

Size: 23×23 cm

Number of pages: 100

Printing: Plantijn Caspari

ISBN: nr 90-9019168-2

Some notes

This book features 21 visual artists from the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany who took part in the exhibitions Abstract Salon Part One (september / october 2004) and Part Two (april / may 2005) in Kunstruimte 09 in Groningen. The exhibitions did not pretent to give a complete overview of abstract or ‘representation-free’ – or whatever you want to call it – art.

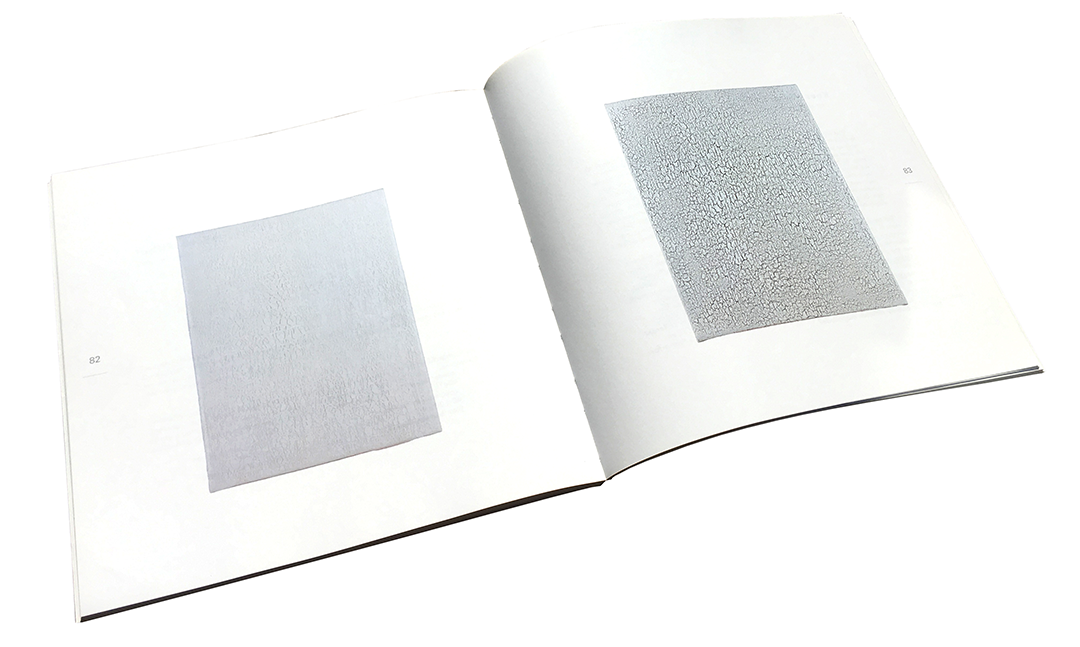

What they did present was a cross section of the way in which ‘representation-free’ art is becommig painted art. Formal, intuitive, conceptual or poetic – it showed a diversity of highly personal ways to shape what’s without representation, as well as a broad range of means and materials.

For the exhibition ‘Part One’ we collected work by Rajlich in The Hague. It was recent work he had left for us with an acquaintance while he was staying somewhere else. In the centre of The Hague above a shop dealing in design goods from the nineteen fifties and sixties, we ended up in a dark, rather small living room. On the wall were some 15 Rajlichs from different periods, from the late sixties until now. In between hung work by Schoonhoven and other abstract and concrete work.

It brought tears in our eyes. That’s when we realized our own motivation for the organizing of the Abstract Salons. While we didn’t have the funds to pay for such a collection of art, what we could do was briefly crate our own living room (without bookshelves, tables, chairs and plants) and decorate it with the art we liked and rarely see get. And whatever the qualifications, interpretations and descriptions one could come up with for the work on show: there were some beautiful pieces of art, a feast for the eye and a joy for the senses.

In a continuing quest for ‘young’ and ‘innovating’, artists and art movements are being superseded and marked as anachronistic increasingly faster. After all, where there’s young and innovating, there’s old and outdated. The average turnover speed of ‘new art’ and ‘youn artists’ is nowadays an estimated two years. The underlying idea for ‘young and innovating’ is the concept that every next generation of artists and ‘new art movement’ can improve on the art produced by previous generations. And that’s nonsense, of course. The development of art is not a linear positive one. In the ‘Abstracte Salon’ participants were not selected for being young or old, but purely based on their work. The fact that it involved older as well as relatively younger artists was more or less a coincidence. Most artists featured in this book are now aged between 45 and 55. And this can’t be a coincidence. While it wasn’t our intention, perhaps the work by artists like these improves with age, just like good wine, amking itunsuitable to act in what is being referred to as the ‘generation gallop’ or to feature amongst the modern artentertainment after shown in museums and art galleries.

We recently took a slightly damaged panel to a sawmill to be trimmed by a few millimetres on one side. ‘Carefull’ we said, ‘it’s a painting.’ The sawyer turned the panel around and around and then said: ‘ so where is the painting?’ (perhaps superfluosly, the paining was abstract: a white surface in oil paint, blending into a pale violet towards the borders).

We also remember a discussion we had with acquaintance about an abstract painting, which went something like this: ‘See, that spot there, it looks like a tree and that makes this a horizon, you see?’ ‘And what if you turn the painting ninety degrees?’ ‘Yes, then it’s a wall or something, or panelling perhaps.’ ‘Culd you just leave the interpretations? And just look at the work itself?’ ‘Well, that makes it just decorative, of course’. And so it went on and on.

We’ve often heard people say at exhibitions ‘I don’t see anything in it’. Sometimes we would answer ‘no, thank goodness’. Then we would point out the beauty of a piece of art, the spatial effect of another piece, its material or perhaps immaterial appeal, the subtle colours, the underlying construction, the illusion of light, the use of classic or new materials, the revelatory new definition of the concept of ‘painting’, etc. In some cases this changed people’s ideas about the work. What we want to say is: somebody looking at the work will need to adapt the same attitude as the one the artist had when he or she made the work: an open mind, focus and time.

The participating artist were ask to summit a brief statement for the book, either a formal discription of their working method, oran explanatory note by a writer about their work, or whatever they could think of. One may have expected that the artists with the most formal work approach would have submitted the most formal texts, and the more intuitive ones a more intuitive text. But they didn’t. It rather seemed as if a certain balance between formal and informal was being sought between word and image.

If we were to define common characteristics in the works presented, we would say it was COLOUR OR MATTER.

Stichting Kunstruimte 09

Jacob van der Veen / jd vos

To Jacob en Joke,

I was pleasantly surprised by Kunstruimte 09’s initiative to pay attention to ‘extreme’ forms of non-figurative art. Perhaps all the more so, since I was very eager to see a response to the ever-present art historians, museum curators and art critics, screaming and shoutingthat the art of paining has drifted too far from every-day reality. At the opening of a photo exhibition here in Groningen I onze heard one of them reproach painters for taking too little account of ‘major social issues’. ‘The world is reeling from war and terror that will have a decisive impact on all ofour near futures. Yet painters merely continue as if nothing is wrong.’ I must honestly confess that I am offended by presumptuous criticsim like this. In itself I can imagine the desire for ‘eine revolutionaire Wende’ in art of painting, inspired by the collective art historical awareness; the memory of the main avant-gardes with their programmes, views and ideologies. It arises from the nation that vital art can contribute solutions, or can at least chip away at social, political or religious dogmas. However, it ignores the fact that all movements stiring up rebellion have eventually been proven ineffective, underlining the futility of projecting former art climates to modern times and the consequences subsequently drawn by artists. Indeed, artists became increasingly individualistic, were less tempted to work as a community, and were increasingly trying to find the truth in themselves. The latter applied particulary to the art of paining. Is seemed to withdraw while painters concentrated on issues that seemed to have a little to do with the world around them. Loss – if you could call it that- even became beneficial. After the art of paining had struggled out of movements such as pop-art, minimal art, conceptual art and other modern art movements and regained its sense of the distinctive qualities of its technique, it increasingly marked out its role vis-à-vis other disciplines.In many ways, the art of painting became the medium suitable for reflection, focus, introspection and (self)reflection. The first response came from photography and video. And perhaps also a certain form of commitent. The opening official I talked about earlier clearly demontrated the general dislike of this new development. ‘Young painters should address social discussions’ – I didn’t quite see why he only addressed young artists and what exactly it was that he expected from them. I have trouble placing comments like this. Why should the art of painting be anything else than it really is? What is it that they want from painters? That he or she comments on the war in Iraq, questions fundamentalism or focusses on more abstract concepts such as ignorance and intolerance? It’s people like these that I feel that understand nothing of the art of painting, understand nothing of the slow speed of the medium and that you need to get away from your every-day problems to be able to create your work. Nor do they understand that you don’t just use your subjects or images, but reader that they slowly present themselves in your work and they can’t be forced in any particular direction. They present themselves as fascinations, amasements and won’t leave you until you’ve put them on canvas.

The criticism is nothing new. When I resently reread Hendrik Werkman’s published letters I came across a passage with Werkman showed the visitor one of his prints. The visitor asked the artist for the social theme in his work. Note that this meeting took place during the war. Werkman writes: ‘I was left speechless. I could only answer that this was nog important enough issue in my work and that I had no interestwhatsoever in depicting the conflict. I did show him the print [….], of a man and a woman in conversation. I explained that the man talks to his wife to tell her to make the vouchers last and that this was a firstclass social issue. But, and the man is right, it seems strange to me personaly that a person is looking for someting like this in a piece of art and can even feel it as a loss if it is lacking.’

What I do know is that academy painting education needs to be revised, that more and more talented artists prefere photography, video and computer aty over painting on an easel and that this affects its quality in general. Consequently, the art of painting is now finding itself in an unfavourable position. But I don’t think it is right to burden it with a problem that shouldn’t be a problem. Any so-called commitment problems exist only in the minds of the art historians and the critics who believe that they can impose something on the art of painting whitch it cannot possibly meet. These are art historians and critics who, perhaps, take too little account of the specific professional and technical characteristics or the painters’ motivation.

I wish you every success in your plans,

Han Steenbruggen

Curator Groninger Museum